Working Diagnosis:

Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy

Treatment:

At the end of our visit, we recommended continuing the scapular brace and encouraged physical therapy. Gabapentin was offered as ibuprofen and acetaminophen were not effective. However, the patient responsibly declined citing concerns with drowsiness especially while operating a plane.

Outcome:

Ultimately, the patient revealed that his mother had facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD). However, given his occupation as a pilot, he did not want to get tested for the same disease. He revealed that he was injecting testosterone to help him.

There was no impact on his ability to fly. The MRI of his right shoulder showed edema of the latissimus dorsi, triceps, and teres major muscles.

Author's Comments:

The most likely diagnosis in this patient is facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. It is the third most common dystrophy and is typically autosomal dominant. 1 in 15,000 to 20,000 Caucasians are affected.1 The disease typically manifests as a gradual progression of descending weakness. The disease starts with facial weakness (often mild and asymptomatic), followed by scapular fixators, humeral, truncal, foot dorsiflexors, and then lower-extremity weakness. The most common initial symptom is difficulty with reaching above shoulder level related to weakness of the scapular stabilizers. The severity of the disease varies as does the onset of the disease. Onset can vary from early infancy to the late fifties. Of note, in 1950, an article described a population from Utah of 1,249 across 6 generations that came from one affected individual in 1840. Of the 240 members, 58 of them were affected. It is the first report that confirmed the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and clinical variability of FSHD.

Clinical criteria in 1991:

1. Onset of disease in the facial or shoulder girdle muscles AND sparing of extraocular, pharyngeal, and lingual muscles and myocardium

2. Facial muscle weakness in more than 50% of affected family members

3, Autosomal dominant inheritance in familial cases

4. Evidence of myopathic disease from electromyography and muscle biopsy in at least one affected member, without biopsy features specific for alternative diagnoses

Since these criteria were released, several reports have described myocardial involvement that call into question the validity of the strict criteria. Instead, an algorithm is suggested:

The patient had a genetically confirmed 1st degree relative (his mother) with clinical features suspicious for a muscular dystrophy.

In most patients with FSHD, the genetic lesion consists of a contraction of the macrosatellite repeat array D4Z4 in the subtelomere of chromosome 4q to less than 11 repeat units. There is a clinically identical, but genetically different variant known as FSHD type 2 that accounts for approximately 5 percent of patients with clinical FSHD.1 The predictor of severity in FSHD appears to be the D4Z4 deletion size and patients with larger deletions are more likely to develop symptomatic extramuscular manifestations.

The treatment for FSHD itself has only controversial results. Albuterol, corticosteroid, and diltiazem have all shown no benefit. A myostatin inhibitor, MYO 029 did not show benefit. Surgical scapular fixation may be beneficial for a select group of patients with FSHD that can tolerate the surgery, postsurgical bracing, and stand to gain from the increased range of motion. Low-intensity aerobic exercise and guided physical therapy strengthening programs is recommended. A study recently demonstrated that, almost counterintuitively, high-intensity training may be a feasible method for rehabilitating patients with FSHD.

Pain is a common complaint of patients with FSHD and the recommendation is to refer to physical therapy as a nonpharmaceutical option and to offer non-steroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for acute pain. Chronic pain can be managed by antidepressants or anti-epileptics.

Respiratory muscle weakness can develop in some patients with FSHD and may be evident only after going through pulmonary function testing. Often, patients present with sleep apnea symptoms: respiratory insufficiency during sleep, daytime somnolence, and nonrestorative sleep. There the recommendation is for anyone diagnosed with FSHD to obtain baseline pulmonary functions.

There is little evidence for structural cardiac abnormalities in patients with FSHD. Conduction defects occur slightly more than the regular population. As a result, the recommendation is to not do routine cardiac testing.

Retinal vascular disease typically affects patients with extremely large deletions. Patients with large deletions should be evaluated by a retinal specialist as screening. Additionally, young patients less than 10 years old with FSHD should be screened for hearing loss.

Editor's Comments:

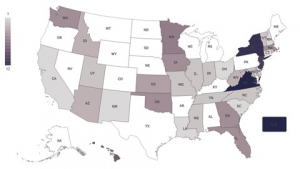

FSHD is the 3rd most common muscular dystrophy and is autosomal dominant. The onset of disease varies from early in childhood to late adulthood with mean onset in the second decade of life. It typically manifests as unrecognized facial weakness with initial complaints of asymmetrical shoulder weakness. The weakness can continue to descend to the trunk, foot dorsiflexors, and overall lower-extremity weakness. Diagnosis can be made through the 1991 diagnostic criteria, but there is a suggested flowchart as well Case Photo #6 . Extramuscular manifestations of FSHD include cardiac, pulmonary, retinal, and otologic. There is no formal therapy for FSHD. However, guided exercise programs, NSAIDs for acute pain, antidepressants and anti-epileptics for chronic pain, and at times, surgical scapular fixation may be of benefit. Scapular braces are typically poorly tolerated although it has been shown to be an effective treatment option in adherent individuals with scapular winging. Screening is recommended for patients with FSHD including baseline pulmonary function tests for all, retinal for those with large deletions, and hearing for younger patients less than 10 years old.

References:

1. Tawil R, Kissel JT, Heatwole C, Pandya S, Gronseth G, Benatar M. Evidence-based guideline summary: Evaluation, diagnosis, and management of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the... Neurology. 2015;85(4):357-364 8p. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001783

2. Pandya S, King WM, Rabi T. Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Semin Neurol. 2008;88(1):105-113. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1040824

3. Corrado B, Ciardi G. Facioscapulohumeral distrophy and physiotherapy: a literary review. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27(7):2381-2385. doi:10.1589/jpts.27.2381

4. Padberg GW, Lunt PW, Koch M, Fardeau M. Diagnostic criteria for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 1991;1(4):231-234. doi:10.1016/0960-8966(91)90094-9

5. Andersen G, Heje K, Buch AE, Vissing J. High-intensity interval training in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy type 1: a randomized clinical trial. J Neurol. 2017;264(6):1099-1106. doi:10.1007/s00415-017-8497-9

6. Martin RM, Fish DE. Scapular winging: Anatomical review, diagnosis and treatments. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1(1):1-11. doi:10.1007/s12178-007-9000-5

Return To The Case Studies List.